April 16, 2014Alan Wanzenberg has long been a champion of early-20th-century Arts & Crafts furniture: “It had moral content and was about how people should live,” he says. Photo by Michelle Rose; Top: In the dining room of a New York duplex apartment, Wanzenberg hung an antique Japanese screen as a counterpoint to the room’s more serene river views. Photo by William Abranowicz

Boredom has its benefits,” writes architect and designer Alan Wanzenberg in his newly released monograph-slash-memoir Journey: The Life and Times of an American Architect (Pointed Leaf Press). “For me, since I could understand and articulate its benefits, I’ve needed what boredom provides — long periods of unstructured time.”

Wanzenberg is not getting much of that these days. Between running his 17-person Manhattan office, working on multiple residential projects (including three large condominium developments), rolling out a collection of lighting for Remains and touring the country to promote his book, unstructured time is in short supply. This mildly irritates the 62-year-old Wanzenberg, who values private time for thoughtful contemplation.

On a recent wet New York City afternoon, he’s sitting in his modernist Hell’s Kitchen office — Jean Prouvé chairs, mid-century sofa, colorful Philip Taaffe works on the walls and piles of books and fabric samples lining the room’s edges — taking some time to get comfortable with the idea of being interviewed, something he clearly doesn’t relish. “Publicity distracts you from a certain level and quality of thinking,” he protests politely.

As Wanzenberg adjusts to the attention, however, he slides back into the seat of his chair. He digresses easily and often. His stories are occasionally hilarious, consistently interesting and peopled with bold-faced names: Andy Warhol, Mick and Bianca Jagger, Fran Lebowitz, Philip Johnson.

The dining room of an apartment in the iconic San Remo building on New York’s Central Park West features a Max Ingrand light fixture, a Sornay buffet, a Hakimian rug, and a James Nares painting that adds a calligraphic flourish. Photo by William Abranowicz

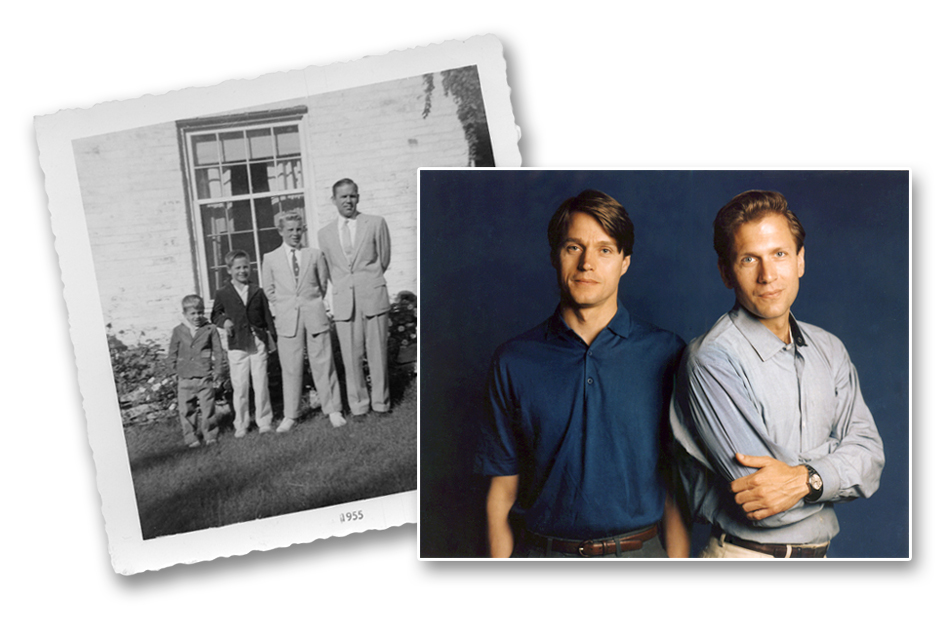

Wanzenberg was born in Evanston, Illinois, the third son of Henry and Doris Wanzenberg — he a civil engineer and mechanical contractor; she a housewife, avid athlete and amateur pianist. “There was enough spread in my brothers’ and my ages that, by the time I was born, a certain fatigue had set in,” Wanzenberg says of his parents. So, as a boy, he was allowed the solitude to which he naturally gravitated. In Journey, he talks about spending this time on long walks admiring the neighborhood’s architecture, which included several Frank Lloyd Wright homes. He also spent hours at the Art Institute of Chicago’s Thorne Miniature Rooms, “a visual treasure of architectural history,” he writes.

The Wanzenberg family spent summers at Castle Park, Michigan. It was in this lakeside resort’s 19th-century rental cottages that he acquired a lifelong respect for fine craftsmanship and vernacular forms, elements that continue to distinguish his architecture and interiors. Still, the young Wanzenberg assumed he’d pursue his father’s trade. A month in an Outward Bound program his junior year of high school expanded his interests, however, and when he left for the University of California, Berkeley, his intent was to study nautical engineering. But he eventually switched majors and graduated in 1973 with a bachelor’s degree in architecture. He went on to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and earned his master’s in 1978.

Wanzenberg spent the next four years in the New York offices of I.M. Pei. It was during his employ there that, in 1980, he met Jed Johnson, then Andy Warhol’s lover and a rising design talent. “Initially I didn’t pay much attention to him because he was quiet,” recalls Wanzenberg. “Andy had three criteria for those he gathered around him: Are they beautiful? Are they famous? Are they wealthy?” Unpretentious and pensive, like Wanzenberg, Johnson was an anomaly among the extroverted Warhol Factory crowd. But he was certainly beautiful.

A staircase, writes Wanzenberg, “is a design element that allows for great invention.” Here, in a New York apartment, he created an innovative statement with lacquered and patinated steel ribbons. Photo by Michelle Rose

Wanzenberg and Johnson began collaborating on design projects, and, over several months, the relationship became romantic. By 1981, the men had left their respective partners, moved in together and established a design and architecture business out of their West 67th Street apartment. They formalized their business partnership under the name Johnson and Wanzenberg in 1982. (In 1987, they would split the firm into separate entities — Alan Wanzenberg Architect P.C. and Jed Johnson Associates — to afford each other autonomy. They continued, however, to collaborate on almost every project and share offices.)

Their first big commission came from Dominique de Menil’s nieces, Christiane Schlumberger and Katie Jones, who were referred to them by Fred Hughes, Warhol’s business manager. Hughes also referred Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall, for whom they designed a New York apartment and, later, a house on Mustique. The two were off and running, eventually developing a blue-chip clientele that included Peter Brant, Beth Rudin DeWoody, Richard Gere and other glitterati. But their success didn’t go to their heads. “We both had a hard work ethic,” says Wanzenberg. “We didn’t see each other as tremendously talented. We weren’t conceited.”

They remained on the periphery of the celebrity hurly-burly, preferring each other’s company to the incessant socializing of the Studio 54 clique. Wanzenberg recalls Philip Johnson’s 90th birthday party at the Museum of Modern Art in 1996. He and Jed talked with each other the entire evening. “Fran Lebowitz said to me, ‘I would never have imagined that two people who spend so much time together could have so much to talk about.’”

Early tragedy had solidified their bond. Eighteen months into their relationship, one of Wanzenberg’s brothers died in a plane crash. “It changed the family dynamic forever,” he says. “It was never the same. That drew Jed and me very close in a very short period of time.” Johnson consoled Wanzenberg and encouraged him to take the time he needed to grieve and heal. “Ironically, it became a kind of handbook for how to deal with Jed’s own death,” he says.

When it comes to kitchens, the architect writes, “I find a natural wood provides warmth and is more forgiving and easier to maintain than painted surfaces.” This upstate New York kitchen features aniline-dyed cabinets. Photo by William Abranowicz

Johnson was on TWA flight 800 when it exploded shortly after taking off from JFK en route to Paris on July 17, 1996. “After he died, I went into shock,” remembers Wanzenberg, who says he was miserable for several years before he allowed himself to return to the world. He is involved with the landscape architect Peter Kelly. “He’s been my compass for the last decade,” Wanzenberg says. “He’s like Jed in his values and his work ethic. Wisely, he never tried to challenge Jed’s influence on my life.”

That authority took a while to overcome. Even after Jed’s twin brother, Jay, assumed the presidency of Jed Johnson Associates (eventually moving out of the offices in 2005), and Wanzenberg regrouped under Alan Wanzenberg Design LLC in 1999, “There was a period when I felt Jed was sitting on my shoulder judging everything I did,” says Wanzenberg. But that is no longer the case. Warhol’s 1987 death liberated Johnson, Wanzenberg writes in Journey. And, in a similar way, Johnson’s death liberated Wanzenberg. “When we were working together,” he says, “Jed would do a lot that was decorative, something that broke the architecture and gave it a counterpoint. That’s not in my DNA. I’m not a guy who does a lot of embellishment.”

Fine craftsmanship spurred both men to champion early-20th-century Arts & Crafts furniture — “For me, it wasn’t just a style,” says Wanzenberg today, “it had moral content and was about how people should live” — and it remains important to him. So, too, does authenticity, a quality that manifests itself in the way his architecture and interiors draw on forms and materials native to their surroundings. No matter what the style, his projects’ sense of place is so pitch perfect, one feels they’ve been there forever. Authenticity is also apparent in the way environments reflect the individuality of his clients. There is never an extraneous item in the room; each piece makes absolute sense. It’s about what’s real and necessary for the space.

When Johnson died, writes Wanzenberg in the book, he “was possibly the happiest I had known him, for he had finally become the man he had always striven to be.” When Wanzenberg is asked if that’s also true of him at this point in his life, the architect demurs. “Of course not! I think I have all the pieces in place, but I’m still working on the connections,” he explains. “I’ve never wanted to go one-hundred-and-eighty degrees with my life. I just want to work on making myself a better person and becoming better at what I do.”