“It’s not as easy as it might look,” says photographer and filmmaker Jerry Schatzberg when asked how he’s been able to take such intimate portraits of rock stars, actors and other celebrities over the years. “You have to get someone in the mood. You have to have your camera ready. You can’t make someone uncomfortable.”

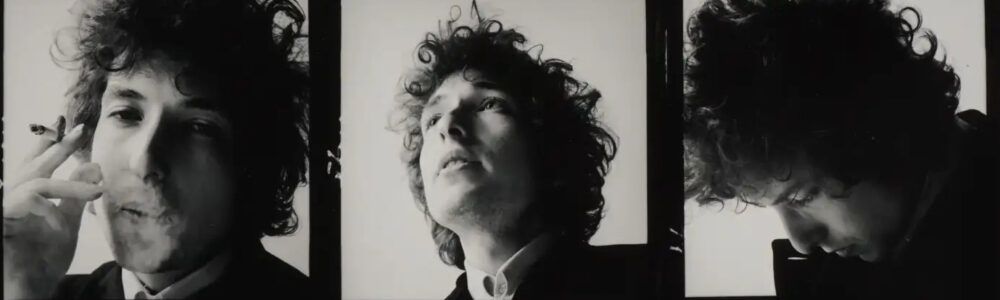

He clearly had iconic folk-rock musician Bob Dylan in the right frame of mind during a legendary shoot in his Manhattan photo studio in 1965. “We hit it off,” Schatzberg recalls.

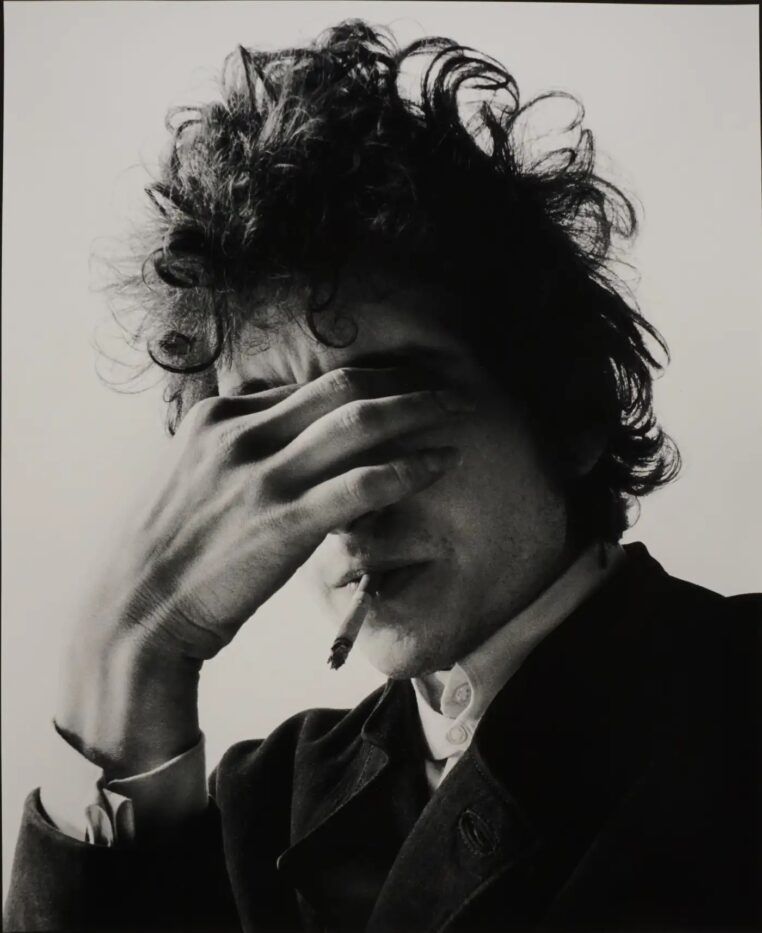

The session yielded some of the most intimate and intense portraits ever taken of Dylan, including the black-and-white gelatin silver print Smoke, which shows him pressing his fingers to his eyes, his brow furrowed and his lips clenching a lit cigarette. We seem to have caught Dylan in a private moment.

“I like the idea that you can make up your own mind about what’s going on in the picture,” Schatzberg says. “He wasn’t posing. I don’t think very many people are going to ask Bob Dylan to cover his face so they can take a picture. It happened, and I took it. And it became one of my favorite photographs.”

It’s an unusual image. Here, we see his hand instead of his eyes. It’s a satisfying trade-off.

This is the hand, after all, with its lithe fingers and long guitar-picking nails, that penned some of the most powerful and poetic lyrics of all time (for which Dylan was awarded a Nobel Prize in literature) and strummed so many memorable songs. The way the light falls, it looks carved out of marble, giving a palpable sense of physicality to the famously elusive musician.

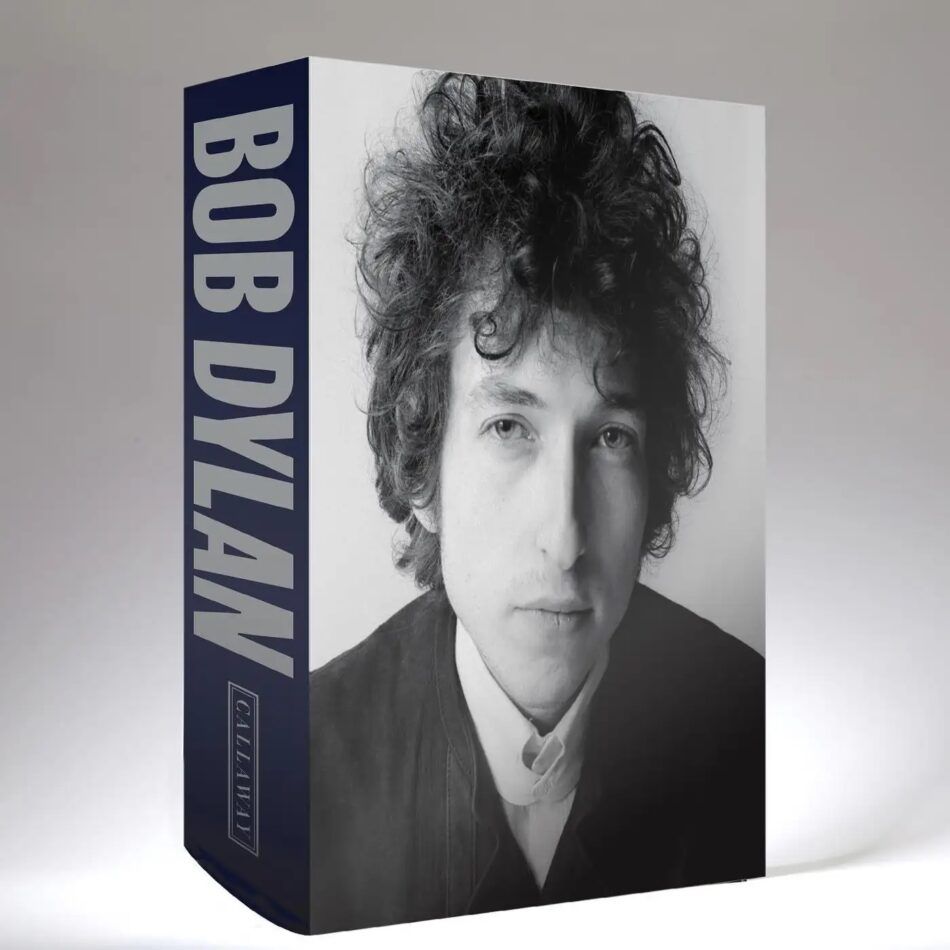

Smoke is one of more than 50 portraits of Dylan in the exhibition “Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the Medicine” at Peter Fetterman Gallery, in Los Angeles. The show coincides with the launch of a major book of the same name, published by Callaway Arts & Entertainment in October. The tome, which span’s Dylan’s career, includes some 600 images, many of which have never been published, as well as commissioned essays by esteemed writers and critics. It’s a kind of unofficial catalogue for the Bob Dylan Center, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which opened in 2022.

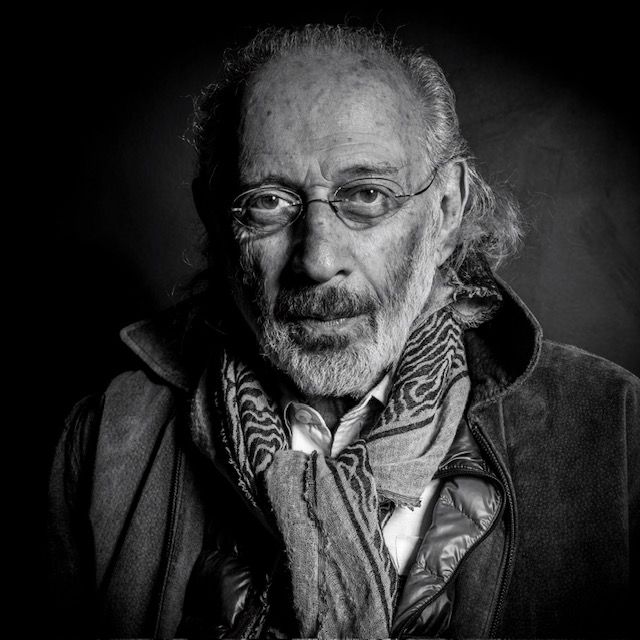

Schatzberg, now 96, is as celebrated for his photographs of pop cultural icons like Faye Dunaway, Edie Sedgwick, Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones as he is for the gritty New York films he directed in the 1970s. He launched his career in the mid-1950s, after talking his way into a job as a photography assistant to William Helburn, who shot for Vogue, Glamour and Harper’s Bazaar.

A New York native, Schatzberg eventually set up his studio on Park Avenue South, where he worked with dozens of models, including the German singer Nico before she joined the Velvet Underground. “She’d call me and say, ‘Jerry, did you listen to Bob Dylan?’ ” he recalls. “And I’d say, ‘I’m always listening to him.’ And she’d say, ‘No, Jerry, did you REALLY listen to him?’ She wanted to make sure I was hearing his words.”

While shooting a band in 1965, Schatzberg overheard rock journalist Al Aronowitz talking about seeing Dylan in concert the previous night. “I figured I had nothing to lose, so I said to Al, ‘Next time you see him tell him I’d like to photograph him,’” he remembers. The next day, Schatzberg got a call from Sara Dylan, the musician’s wife at the time and a former model he had photographed years before. “She gave me the address where he was recording and told me to show up.”

Schatzberg went with his camera the next day. Dylan was in the middle of recording Highway 61 Revisited — one of his earliest electric albums bridging folk and rock music. “I wanted to get him to my studio, and I knew the only way was to take some photos that day that he liked,” says Schatzberg. Dylan did like them: He immediately chose one for the cover of his book Tarantula (published a few years later), says Schatzberg. The photo shoot that yielded Smoke ensued.

“He did wonderful things. Surprising things,” says Schatzberg. “Like, I took my keys out of my pocket and gave them to him and said, ‘Do something.’ He took out a match and lit them. He was very playful.”

They developed a friendship, and Schatzberg continued photographing the singer. For the cover of the 1966 album Blonde on Blonde, Dylan chose an image that Schatzberg took during a wintry outdoor shoot on Manhattan’s West Side.

“Jerry has a kind of zeitgeist touch to him — whatever was going on in creative fields, Jerry was part of it,” says dealer Peter Fetterman, who first met Schatzberg more than 50 years ago while working in the film industry and has represented the photographer for more than three decades. “He’s not just doing commissions to make album covers. There are certain photographers who are not just doing it as a gig. They bring their own kind of personal gestalt. Jerry is one of them.”