A groundbreaking new exhibition is shining a forensic black light on the influence of macabre Gothic art on some of the most radical painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“Gothic Modern: From Darkness to Light,” at Helsinki’s Ateneum Art Museum through January 26, 2025, reframes the origins of modernism, tracing how artists like Edvard Munch, Käthe Kollwitz and Vincent van Gogh drew inspiration from the haunting, mystical imagery of medieval and Renaissance Europe.

The show presents 200-plus paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures and works of decorative art, bringing together modern masters and their Dark Ages progenitors.

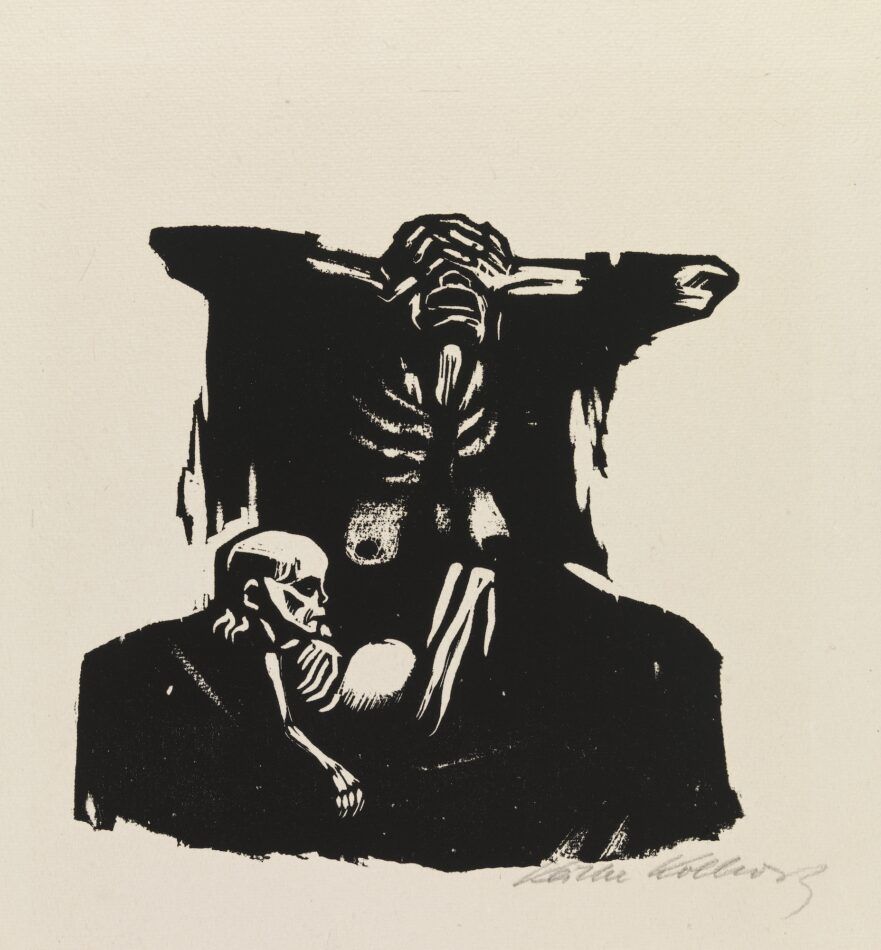

Through Expressionist pieces like Munch’s stained-glass-inspired masterpiece The Sun (1910–13) and Kollwitz’s wrenching Death and Woman (1910), the exhibition uncovers how these artists turned to the Gothic not just as a formal influence but as a wellspring of revolutionary visions of sexuality, war, disease and social norms.

Older Northern European art, with its vivid expressions of Christian devotion and death’s inevitability, was in the zeitgeist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“There were many exhibitions touring Europe at the time, and modern artists began to be interested in Lucas Cranach the Elder, Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein,” explains the Ateneum’s director, Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff, who cocurated the show with art historian Juliet Simpson. “Berlin became the new hub for Nordic artists, and of course, Berlin’s museums were a great source of inspiration as well.”

Organized thematically, “Gothic Modern” creates striking dialogues across the centuries. In one space, Cranach the Elder’s lusty Adam and Eve paintings from the 16th century are placed in conversation with modern reimaginings by artists like Hugo Simberg, Ejnar Nielsen and Max Beckmann, highlighting an enduring fascination with the entangled realms of the sexual and the spiritual.

“Modern artists modified the iconography and altered the meaning of religious themes quite freely, especially Edvard Munch and Helene Schjerfbeck,” says von Bonsdorff. Others grew quite religious themselves. “Marianne Stokes became interested in Catholic Christianity in her later life. Also, Gustave Van de Woestyne went to a monastery for a short stay but left to continue as a painter.”

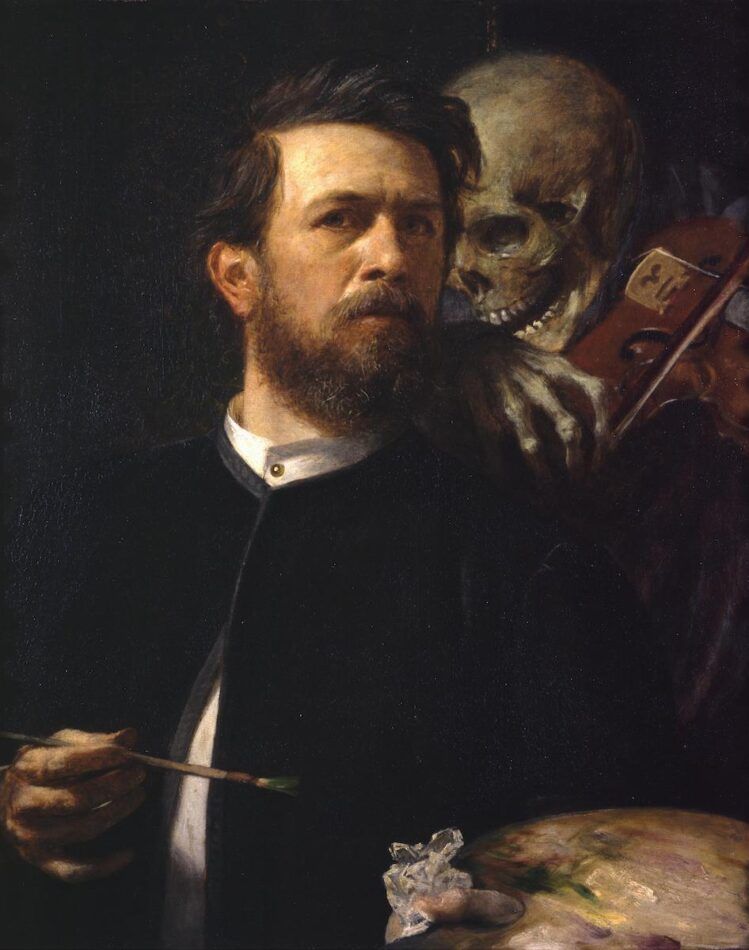

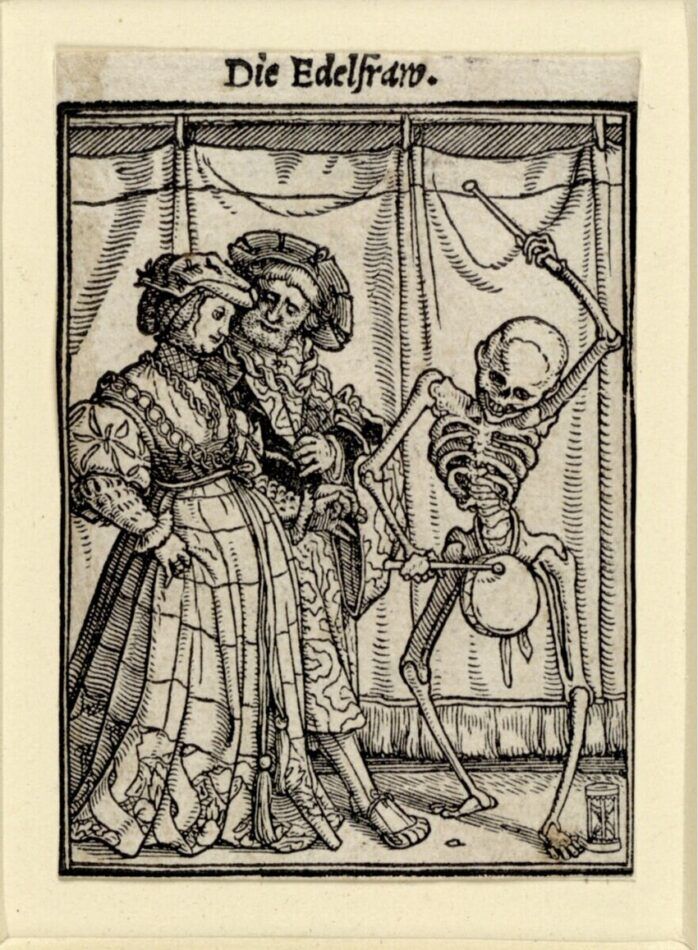

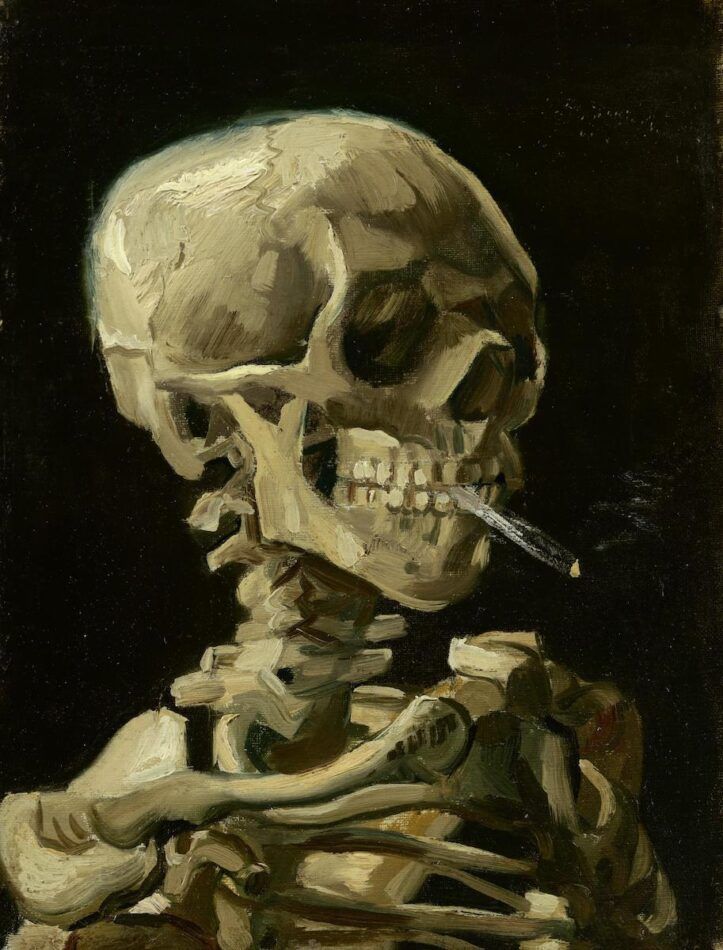

Elsewhere, the mocking specters of Holbein’s “Dance of Death” series (1523–25) find echoes in Van Gogh’s Head of a Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette (1885–86), Arnold Böcklin’s Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle (1872) and Kollwitz’s terrifying depictions of human suffering on an industrial scale.

According to Simpson, the show demonstrates how Gothic themes remain relevant but resonate differently in different time periods and cultures. “It’s about adaptation, and it’s about the power of the Gothic to work, be reimagined across borders, but also to be adaptable to particular, even local, cultures of place and identity,” she says.

Indeed, the exhibition challenges the conventional view of modernism’s linear, break-from-the-past progression, revealing how artists throughout Europe were tapping into a shared Gothic visual language to grapple with the tumult of their time. In an era marked by the rise of nationalism, industrialization and world war, the Gothic offered a time-tested means to express the darker currents of the human experience.

Following its debut in Helsinki, “Gothic Modern” will travel to the National Museum in Oslo and the Albertina Museum in Vienna, offering audiences across the continent a new perspective on the gore-obsessed roots of modern art. Likewise, as the curators point out, in our current age of uncertainty and social unrest, the answers we seek may lie not in the future but in the shadowy recesses of the medieval past.

Below, we take a closer look at a few Gothic-modern innovators and their 15th-century forebears.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528, Germany)

One of the most celebrated Northern Renaissance painters and printmakers, Dürer worked in a naturalistic style similar to that of his Italian contemporaries, while using the darker tones and subject matter of his fellow Germans.

Dürer’s haunting woodcuts and engravings, such as his “Apocalypse” series, present unsettling images of death, the supernatural and societal upheaval, which impacted later generations of European artists as they grappled with the traumas inflicted by rapid modernization and weapons of mass destruction.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553, Germany)

In his provocative Adam and Eve diptych (ca. 1530), Cranach, a giant of the Northern Renaissance, explored the intersection of eroticism and religion. His boldly sensual depictions of humanity’s first lovers, sprinkled with a dash of the demonic, set the stage for modern artists to revisit these primordial themes.

Cranach’s 1530 nude depiction of the ancient Roman noblewoman Lucretia in the process of stabbing herself to death similarly combines scariness and seduction.

This fascination with mingling the sacred with the profane was picked up by later generations as they contemplated relationship roles in the age of psychoanalysis.

Hans Holbein the Younger (circa 1497–1543, Germany)

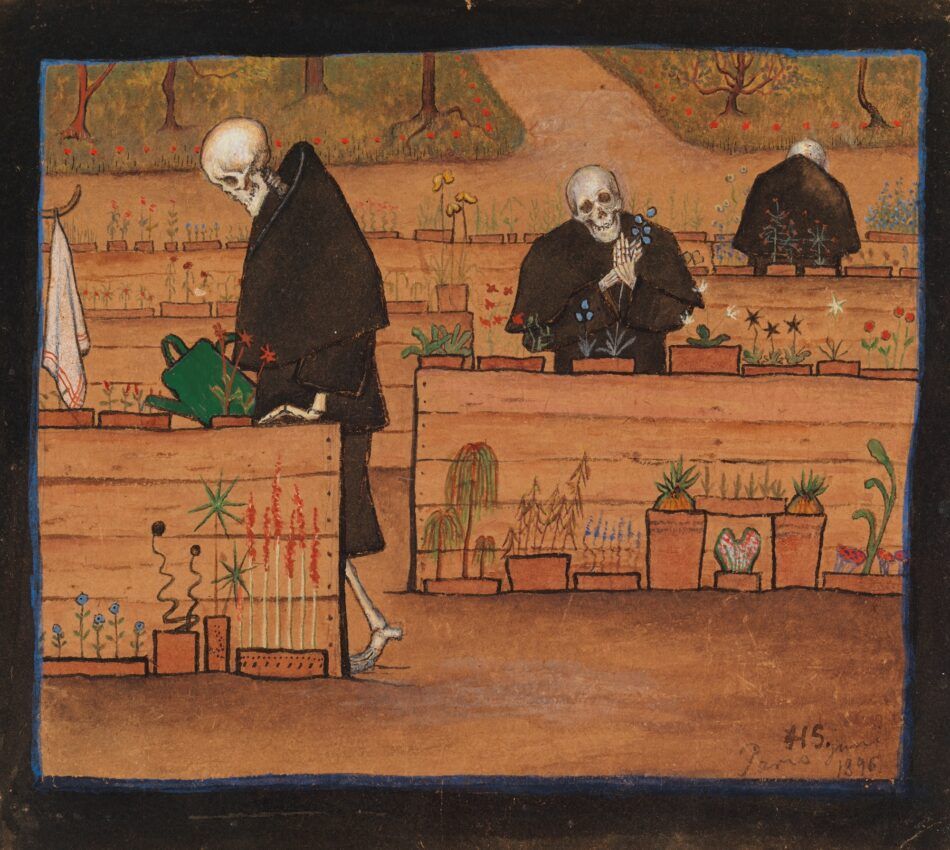

Best known for his penetrating portraits of English royals and aristocrats, Holbein also created the seminal “Dance of Death” series between 1523 and 1525, offering a darkly comic take on the danse macabre motif.

His smiling skeletons, indiscriminately ushering everyone from farmers to nobles to their graves, served as a touchstone for modern artists like Vincent van Gogh and Käthe Kollwitz as they explored the absurdity of life on earth and its inevitable end.

Vincent van Gogh (1853–90, Netherlands)

Van Gogh’s wry Head of a Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette (1886) echoes Gothic artists’ fascination with mortality. Evoking Holbein’s “Dance of Death,” the grinning skeleton embodies Gothic art’s capacity to find both the comic and the tragic in life’s journey.

Van Gogh’s well-known intense, emotive style — saturated with a sense of the supernatural — was hugely influential on later Expressionist painters.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945, Germany)

A master of German Expressionism, Kollwitz channeled Gothic art’s emotional power in raw and heart-smashing works like The Downtrodden (1900), The Survivors (1923) and Hunger (1923).

Her stark depictions of starvation, poverty and collective struggle use Gothic visual themes to offer a poignant commentary on social injustice in the early 20th century.

Marianne Stokes (1855–1927, Austria)

Typically labeled a Pre-Raphaelite, Stokes is reappraised in “Gothic Modern” as a conduit for the Gothic influence on modernism. Paintings like Madonna and Child (1909) and Death and the Maiden (ca. 1908) fuse Catholic iconography with a distinctly modern sensibility.

Stokes’s work demonstrates how medieval imagery provided artists with a rich visual language with which to explore evolving notions of gender, identity and transcendence.

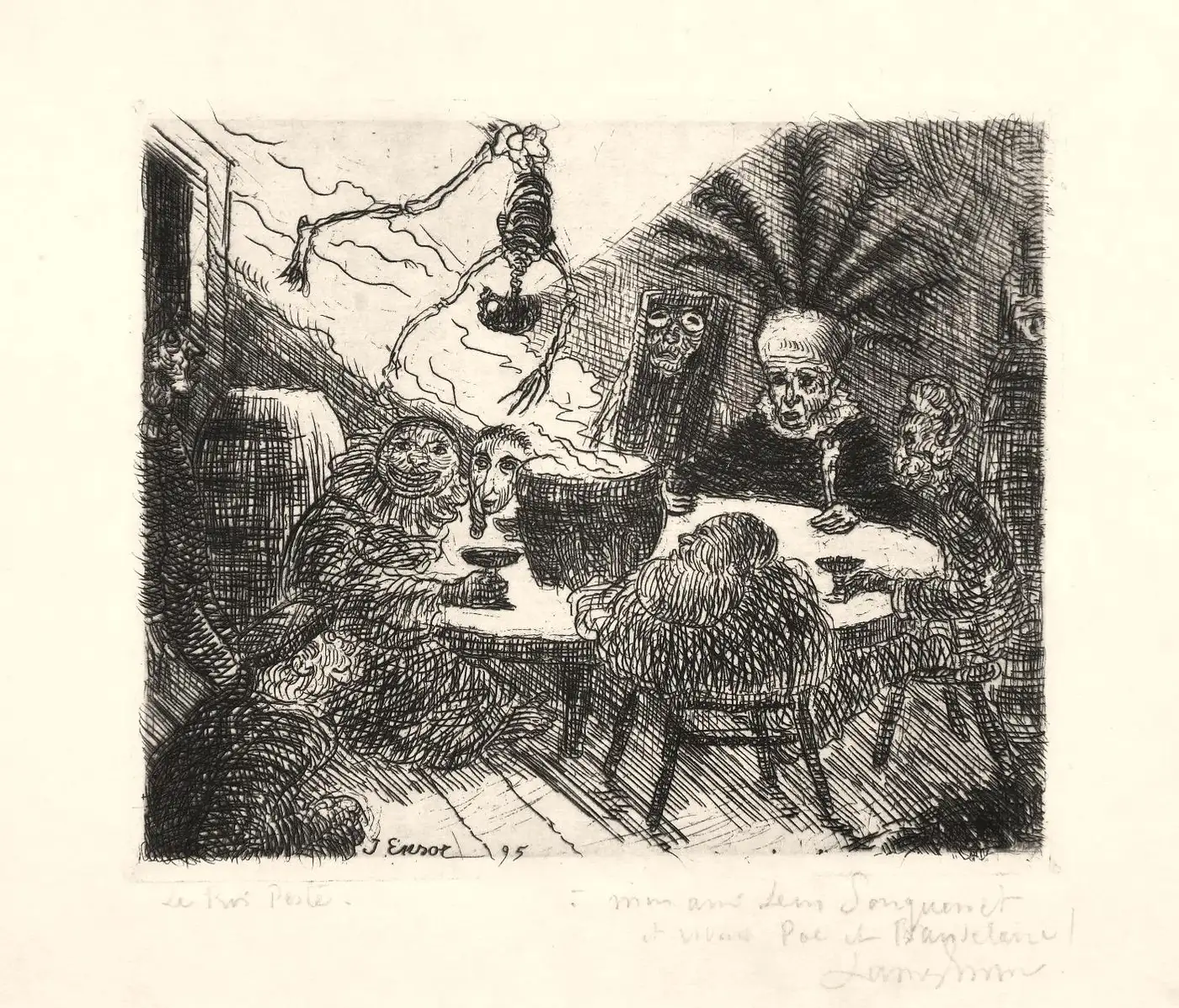

James Ensor (1860–1949, Belgium)

Belgian Expressionist Ensor’s carnivalesque paintings channeled the Gothic fascination with the grotesque and the darkly fantastical. Works like Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889 merge religious iconography with a subversive black humor, evoking the medieval tradition of the “dance of death” in a cacophony of eerie masks, skeletons and costumed figures.

Ensor’s hallucinatory, nightmarish style offers a Belgian take on Gothic art’s ability to unsettle and provoke, introducing a sense of the uncanny and the irrational to the world of modernism.

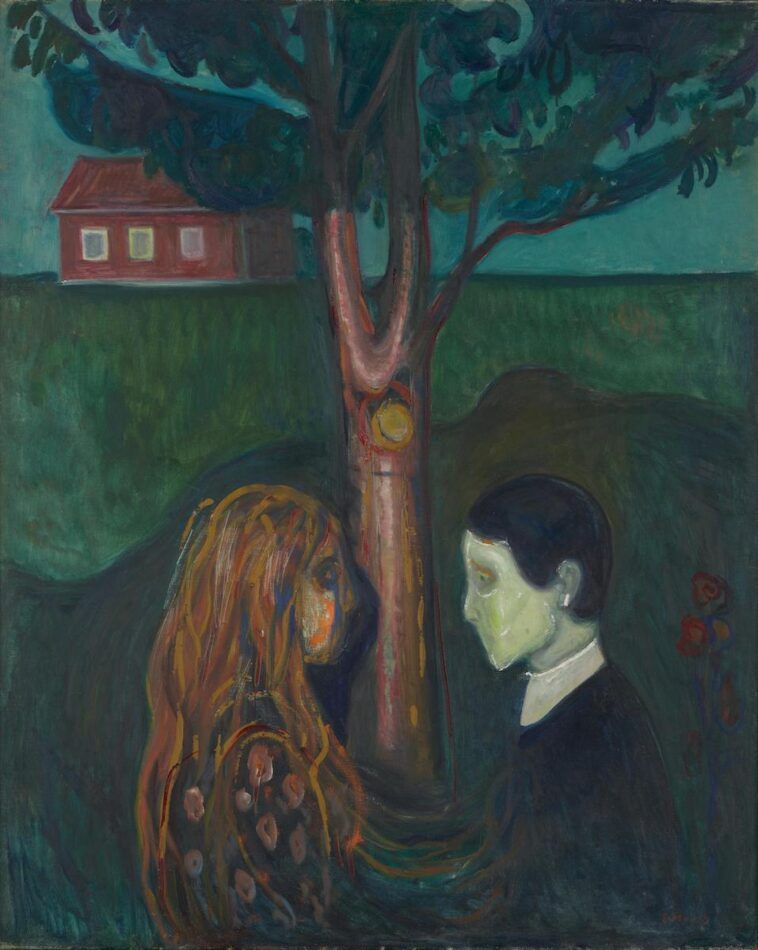

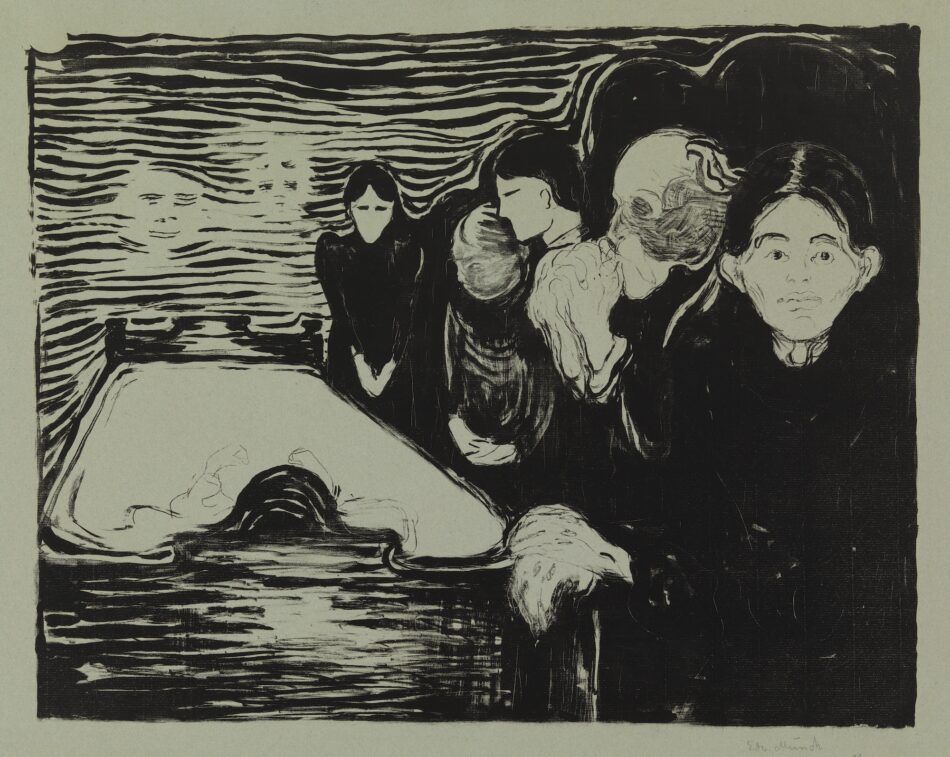

Edvard Munch (1863–1944, Norway)

Long viewed as a solitary Nordic pioneer of Expressionism, Munch is reassessed in “Gothic Modern” as an artist steeped in the visual language of medieval and Renaissance Northern Europe.

Works like By the Deathbed (1896) and Eye in Eye (1899–1900) reveal his deep engagement with themes of death, the psyche and the spiritual.