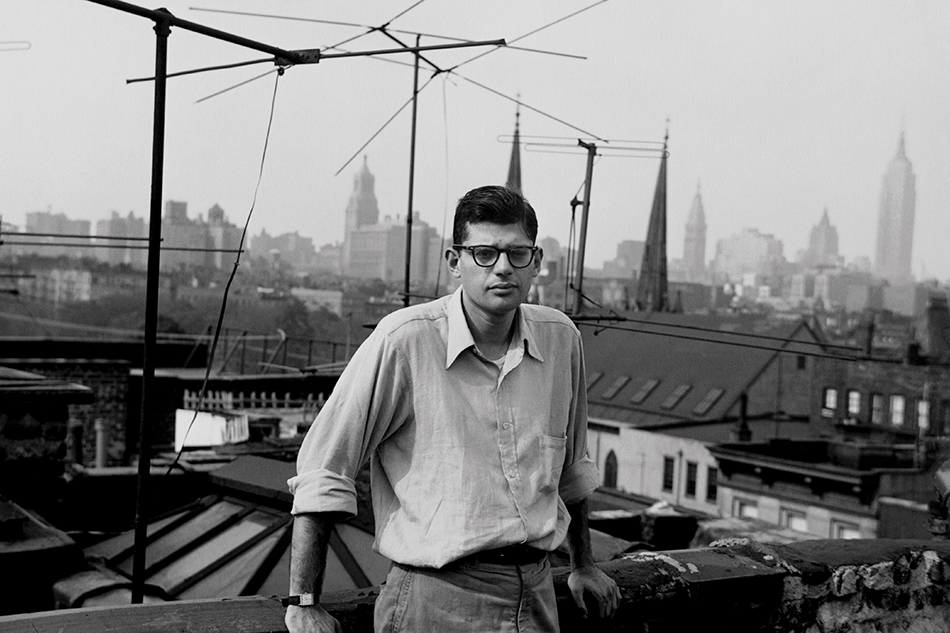

April 2, 2014Stonehill, who has lived in Greenwich Village for nearly 50 years, has put out three other books on New York City (photograph by Alexandra Stonehill). Top: Cafe Figaro (detail), 1965, by Robert Otter, is one of many images in the book offering a bygone view of the neighborhood. All images courtesy of Universe/Rizzoli

At first blush, Judith Stonehill seems as reserved — almost flinty — as her 1834 Charles Street townhouse in Greenwich Village, whose Bauhaus-spirited interiors are punctuated by caramel Barcelona chairs and a black Tobia Scarpa ensemble in the front and back parlors. “People say ‘You’ve become so mid-century!’ ” Stonehill says as Beau, the lab-and-pitbull mix that belongs to her daughter, the photographer Alexandra Stonehill, begs her to toss a ball underneath the Mies sofa. “Well, we bought them in the mid-century,” she says rather archly.

But Stonehill’s quiet, warm persona gracefully unfolds like the pleats on her Issey Miyake skirt. Currently she’s fresh off the publication of Greenwich Village Stories: A Collection of Memories (Universe/Rizzoli), a collaborative effort between her and the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP), of which she’s a longtime member and past president. A tribute to the cultural heritage of her surroundings, the new book is a remarkable array of first-person recollections by musicians (Lou Reed, written shortly before his death), writers (Andrew Solomon), designers (Donna Karan), actors (Patricia Clarkson) and restaurateurs (Mario Batali), as well as the occasional store owner and neighborhood habitué. Malcolm Gladwell writes ruefully of the perfect apartment that got away, while Vanity Fair editor-in-chief Graydon Carter offers a six-line ode to the neighborhood he calls home: “In an age of cities/there is just one village/that is known by people the world over…” “Is it a poem?” asks Stonehill, the highly literate longtime co-owner of the late, lamented New York Bound Books in Rockefeller Center. “I don’t know…but I love it.”

To illustrate the book, Stonehill fille contributed photos of her own and unearthed forgotten images by Robert Otter and Berenice Abbott as well as drawings and paintings, both raffish and exquisite, by Saul Steinberg and Milton Avery, among others. Like these artists, Judith Stonehill knows her subject well: She and her late husband, the noted architect John Stonehill, moved into their Federal-style townhouse (which includes a garden carriage house once rented to Diane Arbus) in the neighborhood’s then-ungentrified western reaches more than four decades ago. And, like any longtime homeowner, she has her habits — when visitors leave, she always reminds them to rub the bronze door-knocker and whisper “In bocca al lupo” — an Italian phrase for “good luck.”

Recently Stonehill spoke to Introspective about putting together the book (all the royalties of which go directly to the GVSHP), living for nearly half a century in the Village and why change isn’t always a bad thing.

A detail of a 1934 map by the illustrator (and master puppeteer) Tony Sarg shows how the streets of the neighborhood famously fall off the city grid west of Sixth Avenue.

You’re well known as a preservationist. What prompted you to embark on this book?

Well, let’s first go back and ask how long have I been involved with the Village. Because everyone here has a story. We moved here in 1968 when we fell in love with a house. We bought it the day after we saw it. At the time, we were living on Lexington Avenue and 81st Street. My husband had no interest in buying a townhouse. On the way down to see the house, he said, “Do you know what a fool’s errand is, sweetheart?” And here I am, 46 years later.

How have you changed as a person after living for almost a half-century in Greenwich Village?

I always thought I was a good liberal, but the Village has made me even more accepting. It has this certain quality — it doesn’t judge people. The thing about the Village is that it is like the people themselves. It’s quirky. When we moved here, The New York Times considered it an “undeliverable” area. I wondered: Were we too old to live here? I was 29 at the time. Don’t forget: In those days, women wore gloves everywhere.

Was there a story in the book that particularly resonated with you?

I love John Guare’s piece, not only because it arrived on my iPad when I was in China, and, after reading it, I thought to myself, I’m going to be able to make this book a reality, but also because of his story of finding his apartment, a fourth-floor walk-up, across the street from which Lanford Wilson lived. The two of them would open their windows and type ferociously in competition with one another.

Also Tom Fontana, when he recalls seeing Lillian Hellman and describes how she still walks the streets although she’s long been dead. That says it all. And part of it is because the architecture is still the same, and it’s very easy to envision these wonderful ghosts walking these streets. It’s all so vivid and alive here.

A statue of General Philip Sheridan presides over Christopher Street Park, whose fence is 130 years old (photo by Alexandra Stonehill, 2013).

Do you have a favorite walk or haunt in the Village?

I actually like West 10th Street. It reminds me of everyone from the painter John Sloan, who also wrote his diaries and painted his incredibly authentic depictions of the neighborhood there, to Marcel Duchamp, who not only lived there but played chess across the street at the Marshall Chess Club. About five years ago, I wandered in there and asked if anyone had ever played against Duchamp, and an elderly gentleman claimed he beat him when he was ten years old — something that I found very dubious.

Were you ever concerned that many of the stories might become a bit maudlin in bemoaning how the Village has changed?

Of course, there is at times a bittersweet quality. I miss the venerable bookseller Dauber & Pine or Alfredro, a quintessential trattoria on Hudson Street. You saw everybody there. I know of one couple that made a reservation for every Tuesday night for the rest of their lives. But then I think of the High Line or all the small green parks in the East Village or Father Demo Square Park, which was once such a dusty place. Now it’s an umbrella of trees. People worry about all the fashion stores on Bleecker Street, but they restored the buildings, and they’ll eventually move somewhere else. At this point in my life, I’ve seen things change and change again.