September 19, 2021Virtual space increasingly overlaps with our daily realities, most recently with the explosion of NFTs on the art market, shifting ideas of where art is made, collected and exhibited. The metaverse — a term for a fully formed online existence coined by Neal Stephenson in his 1992 sci-fi novel Snow Crash — is now a ubiquitous concept, with virtual reality, augmented reality and other technologies contributing to the expansion of the online world.

Now, the metaverse, and the role that NFTs may have in it, are inspiring artists to examine its strange and powerful possibilities.

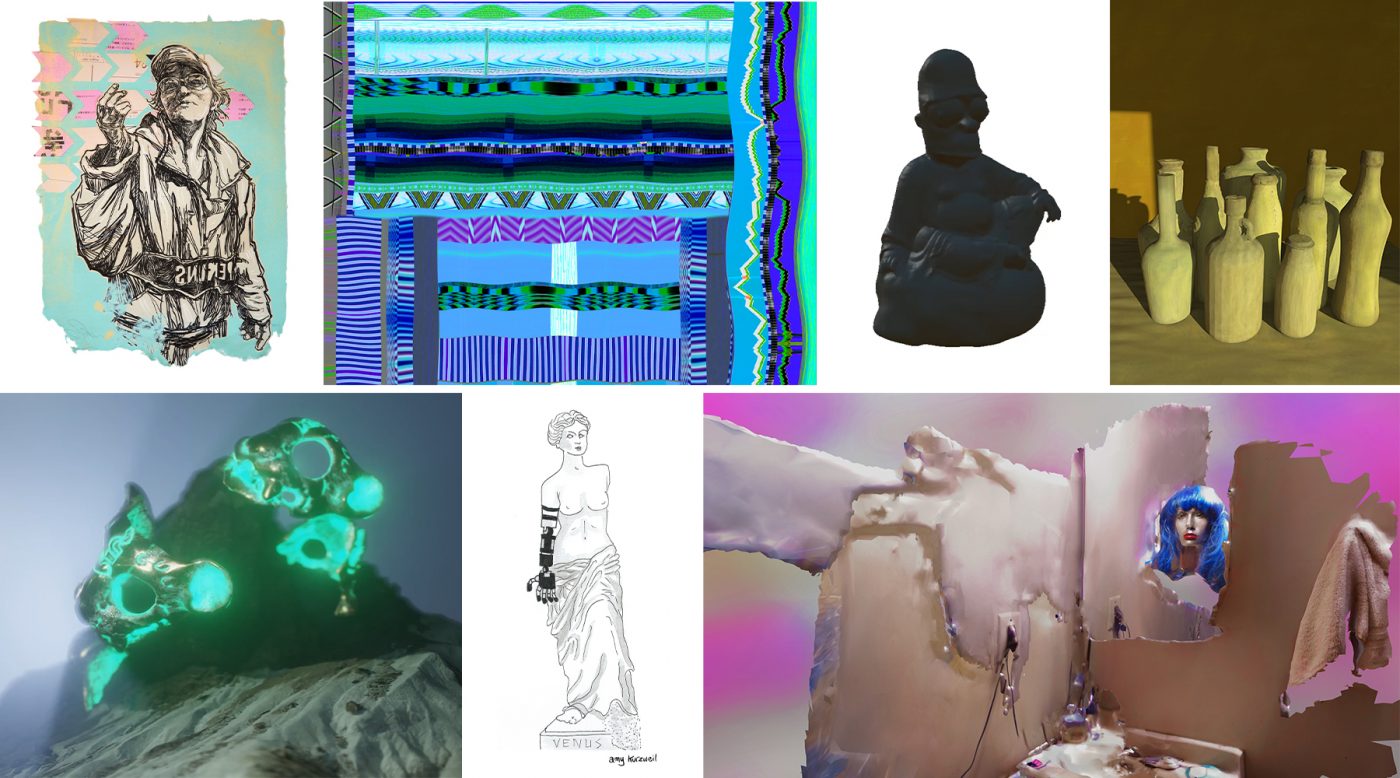

Curator, writer and artist Katie Peyton Hofstadter brings the blurred boundary between the digital and physical realms into sharp focus in “Metaglyphs: Invitation to The Voyage,” the latest exhibition on 1stDibs’ NFT Art platform. The show and auction feature 10 artists whose latest work can best be described as “metaglyphs,” or art that can exist simultaneously in both spaces.

“I selected artists who were probing their own fascination with technology and the metaverse, and throwing a wrench into things,” Hofstadter says. “The work might appear to say one thing, but it’s also looking in another direction. I like what [poet and essayist] Mary Ruefle said about poetry: ‘It is not what a poem says with its mouth, it’s what it does with its eyes.’ To these artists, the metaverse isn’t there to replace reality. It’s there to probe it, to deepen it, to create space for new questions.”

Pieces by Morehshin Allahyari, FakeShamus, Carla Gannis, Claudia Hart, Amy Kurzweil, LoVid, LaJuné McMillian, Alfredo Salazar-Caro, Savannah Spirit and Swoon offer varying perspectives on digital realms.

Alfredo Salazar-Caro, who works as an artist in Mexico City and New York and codirects the VR-focused Digital Museum of Digital Art, is exhibiting Achik’ Mask 1. Based on a scan of a jaguar’s face on a Maya urn, it is a 3D print turned into a bronze sculpture. The jaguar mask is sold with Salazar-Caro’s three animated NFTs, which feature this same figure floating in desert landscapes.

The mask also has a presence in Salazar-Caro’s VR documentary Dreams Of The Jaguar’s Daughter, in which viewers are guided by Achik’, the spirit of a Maya girl, through her dream-like memories of her journey from a Guatemala jungle to an Arizona desert. This jaguar figure could thus be said to bridge the spiritual and earthly realms as well as the virtual and tangible ones.

Morehshin Allahyari, who grew up in Iran and is based in New York, also explores what it means to reproduce cultural objects through 3D scanning. In her research into what she terms Digital Colonialism, she explores the use of scanning in archaeology and its tendency to replicate the power dynamic between researchers and the objects they are preserving while also creating a virtual presence for artifacts that are sometimes lost in the physical world. Related to this, her series Material Speculation: ISIS (2015–16) uses 3D modeling and printing to reconstruct antiquities in Iraq destroyed by ISIS fighters.

In “Metaglyphs,” she returns to some of her earliest 3D printing. “One of the first things that I thought about with a 3D printer was, ‘What would happen if I used this machine to 3D print objects or things that are unwelcome or forbidden in Iran?’ ” she says.

Her “Dark Matter” series playfully mashes up these taboos in such new works as Dog (combining a pet dog, a large dildo and a satellite dish) and Barbie (merging a Barbie doll with a VHS tape). Their virtual and physical manifestations are forms of resistance, documenting the personal possessions that are made political under restrictive governments in Iran, Saudi Arabia, North Korea and China.

Since the early 2000s, LoVid — the New York–based art duo Tali Hinkis and Kyle Lapidus — has spanned the digital and analog planes, frequently in performances where feedback loops generate a constant interchange of experiences. As they explain, “We make work that translates mediated experiences into tactile materials and vice versa.” Their performance practice regularly includes hand-built video synthesizers. For The Other Side of Ground (2010) in “Metaglyphs,” for instance, they used the synthesizer to compose a cascade of vibrant colors collaged from video screen grabs.

Each of LoVid’s NFTs in “Metaglyphs” attempts to channel to new audiences the “unique moments” they create in their performances and videos. Their Noise Shelf (2020) is both a stained-glass object — its design based on a video screenshot — and a digital animation that seems to serendipitously catch the light.

Claudia Hart has been working with emerging technology since the 1990s, when she was one of the earliest artists experimenting with virtual imaging. This year, the New York artist wrote A Feminist Manifesta of the Blockchain, asserting that an NFT “culturally defines a computer model . . . as being on par with physical things, in the way that mechanical reproduction culturally produced the recognition of copyright.”

In “Metaglyphs,” she presents a series of “Digital Combines” that investigate ownership and authenticity, using physical and NFT pieces created from the low-quality imaging of online video games to reconstruct still-lifes by Matisse, Morandi and Picasso.

“I started as an art historian, then studied architecture and ended up as a self-taught geek and simulations-technology expert,” Hart says. “These paintings synthesize everything I’ve ever known into one thing, and I think that emanates from them.”

Brooklyn-based Carla Gannis, who has been exploring digital media since the late 1990s, also reflects on art history. Her “Origins of the Universe” series featured in “Metaglyphs” references Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866) — a closeup painting of the female anatomy that scandalized Paris 150 years ago and is censored on social media today — through a 3D-printed smartphone holder in the form of a nude woman lying on her back. “In my version of an origin narrative,” she says, “I have expanded Courbet’s ‘world’ to a universe, a universe positioned between a woman’s legs, looping videos of the cosmos on an iPhone.”

Also part of “Metaglyphs” is her “Yonder” series, which involves digital C-prints based on 3D iPhone scans. Here, Gannis combines animation, digital painting and AI-generated imagery to create a surreal representation of herself in a virtual space that is at once close to and separate from us.

Savannah Spirit, based in New York, is similarly considering the body in digital space and the complex relationship between maker, viewer and object. For “Metaglyphs,” she is showing selections from “I Am My Own Muse,” part of a self-portrait project she’s been working on since 2014. Her black-and-white images of her body, accented with contrasting light and shadow, confront the stigmas around female nudity.

“At first, it started as a way to combat censorship on social media. But then, I quickly realized that this series is about claiming ownership of my body, myself,” Spirit says. “The art nude is often objectified and sexualized, especially through social-media channels and online. My intention is to be my own object of desire, putting my womanness on display, looking at myself from all different angles.”

The movement of the body and the representation of it in digital space are central to the practice of LaJuné McMillian, a New York–based artist who created the Black Movement Project, an archive of motion-capture data from Black performers, to address their underrepresentation in such databases. In “Metaglyphs,” McMillian, who identifies as “they,” is exhibiting self-portraits made with the video-game-design platform Unreal Engine.

“As an artist and as someone who is working as a technologist, I realized that one of the largest problems with working in the tech sphere, and working alongside performers and dancers, is that they become the object of a piece, and they become less human,” McMillian says.

Using their own image, they are “figuring out ways to bend those boundaries and to see the human center of everyone involved.” For McMillian, NFTs are a new experimental space where “being part of the conversation and the discovery process is important.”

“We want smart artists engaging with new technology because artists bring a creative and critical vision that corporations and financiers don’t,” Hofstadter says. “Most of these works are being auctioned to support larger projects, which is exciting.” While the shape of the metaverse and art’s presence in it are evolving, these artists transport viewers into a liminal space between the world we know and the one still being created.