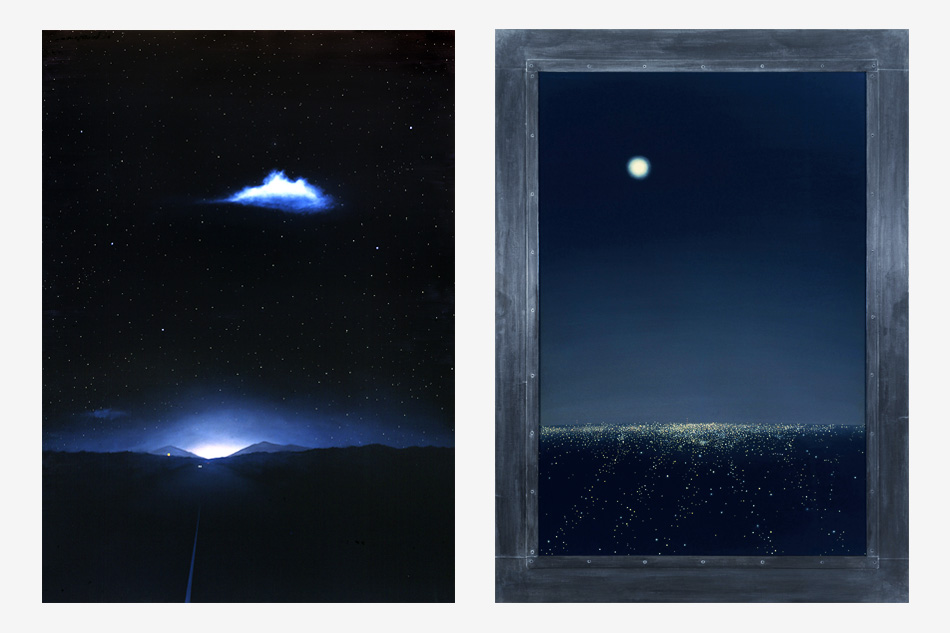

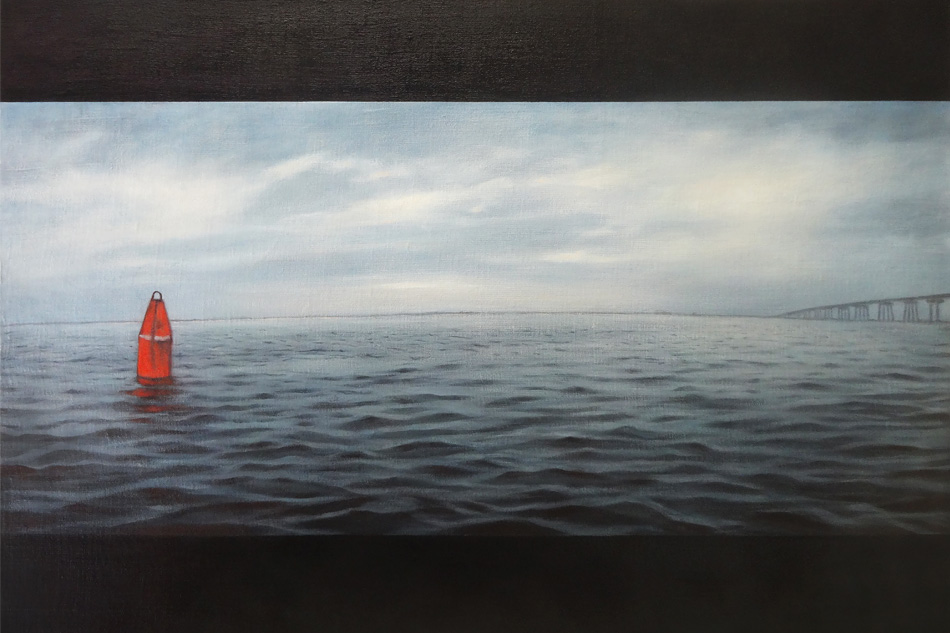

December 5, 2016A show presented jointly by New York’s Nohra Haime and Adelson galleries, on view through December 24, celebrates the work of contemporary artist Adam Straus, whose beautiful, but often just slightly off, landscapes serve as subtle critiques of 21st-century apathy in the face of environmental degradation (portrait courtesy Nohra Haime). Top: Skies, 2012, on display at Adelson (all artwork © Adam Straus).

In this current golden age of contemporary art — with its focus on abstract, conceptual and figurative works — it is either extremely old-fashioned or extremely avant-garde to take on landscape paintings. And yet, Adam Straus has been bravely pursuing this underrepresented genre for more than 30 years, bringing a modern, dark humor and deep social commentary to otherwise sublime and transportive imagery.

More than 50 of Straus’s works are on display now through December 24 in an exhibition presented jointly by two neighboring galleries at 730 Fifth Avenue. Nohra Haime Gallery is showcasing Straus’s oeuvre from 1979 to 2016, including early and little-known photography and sculpture, while Adelson Galleries is focusing on more recent paintings and works on paper from 2011 to the present.

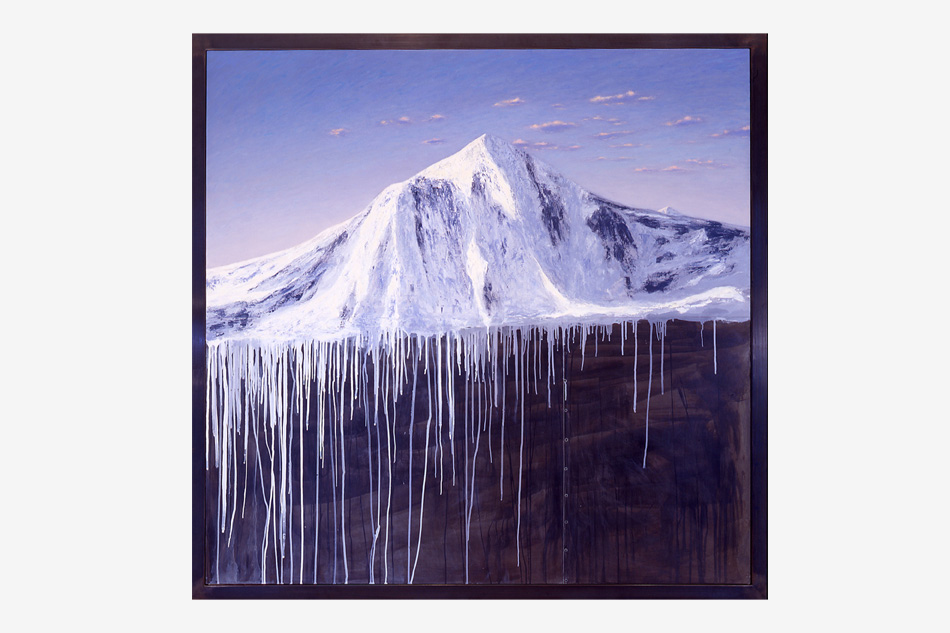

Best known for his atmospheric paintings of the natural world, Straus often works from found photographs and then adds images or uses techniques that suggest there’s more to his stunning scenes than meets the eye. McStop, from 1993, portrays a nocturnal rural scene that seems quietly romantic until one notices the golden arches of McDonald’s glowing on the horizon; in the 2001 Summit: Melting, Straus drips white paint from the top of his depiction of a regal arctic glacier directly onto the picture’s thick lead frame, suggesting that the ice is suffering the effects of climate change. In Toxic Run-Off: Water Lilies, from 1999, Monet-like ponds have their peaceful natural beauty subtly marred by the unnatural colors of fertilizer contamination.

Matterhorn, 2014, is one of the works currently on view at the Nohra Haime Gallery, which is showing pieces from across Straus’s nearly four-decade career.

Gallerist Haime characterizes Straus as a “master of light” and someone who “has always been concerned about mankind’s effect on nature.” She also notes what she calls “his rebel touch.” The son of a community activist, Straus, 60, traces his interest in the natural world to his mangrove- and beach-filled boyhood in Key Biscayne, Florida. There, he roamed free in his 12-foot aluminum motorboat, fishing, snorkeling and immersing himself in the surrounding flora and fauna. “We just knew water and swimming — we could swim before we could walk,” he recalls.

Even then, in the 1960s, Straus remembers, his family was concerned about the dramatic changes already happening to the coral and fish population in Biscayne Bay and the nearby Bahamas. He now makes his home near the Peconic Bay on the North Fork of Long Island, an area that reminds him of Florida and is also being affected by extreme weather and climate change. So it is no surprise, he says, that as a landscape painter, “a social consciousness has fueled just about everything I’ve done with art.”

Straus never thought he would become an artist. He began turning towards creative pursuits in his late teens, however, when an interest in nature led him to take pictures of landscapes and wildlife. Later, while sitting in on a photography class at the University of Florida, where he was studying zoology, he recalls being struck by Duane Michals’s “Things Are Queer,” a seminal 1973 nine-photograph series of pictures that played with the concept of perception and reality. “I realized what you could do with imagery at that point,” he says. “The incredible storytelling and that it could be so far beyond landscape and nature. It could have this narrative and brilliance and poetry.” Straus went on to earn a MFA at Florida State, branching out into painting and what he describes as “dark and dangerous” sculptures using railroad spikes and sheet lead covering that bring to mind Robert Rauschenberg’s “Combines.”

“A social consciousness has fueled just about everything I’ve done with art.”

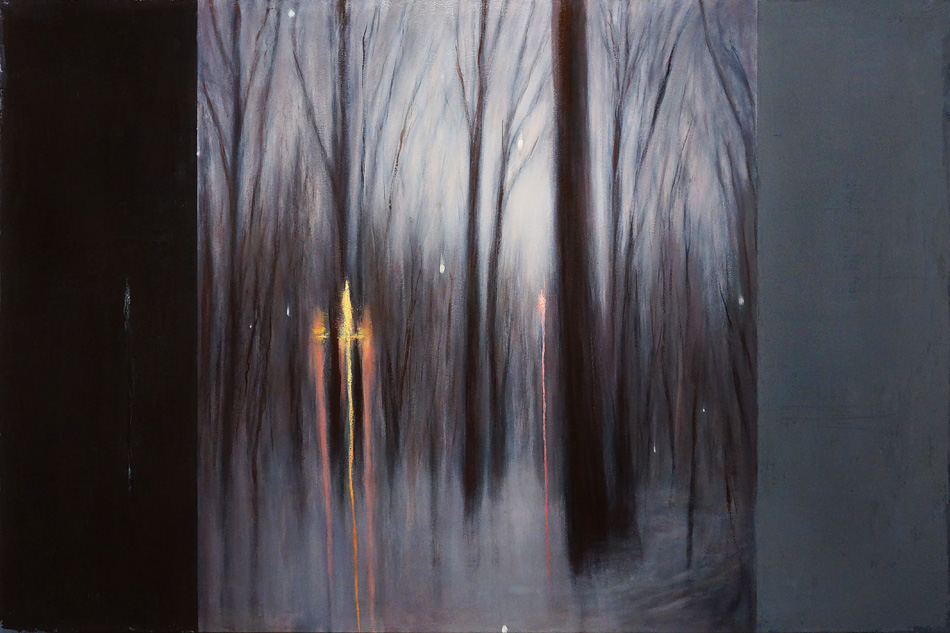

Two human-size sculptures on view at Nohra Haime, Treasure Box with Fool’s Gold and Prison-Space, made of painted black wood, lead and steel, debuted in Straus’s first show, at an East Village gallery in 1984. Straus was still living in Florida at the time, painting houses and doing odd jobs, but he would regularly drive up to New York to show his slides to the galleries. He began to focus on painting in the mid-1980s — because, he admits, it was less labor-intensive than the sculptures — starting with intimate, dark nocturnal landscapes like Gun Shot, from 1986, which he made by layering coat after coat of black house paint over white house paint. Nohra Haime saw some of these early works and offered him a show. So, in 1990, Straus moved to TriBeCa and started frequenting galleries and museums.

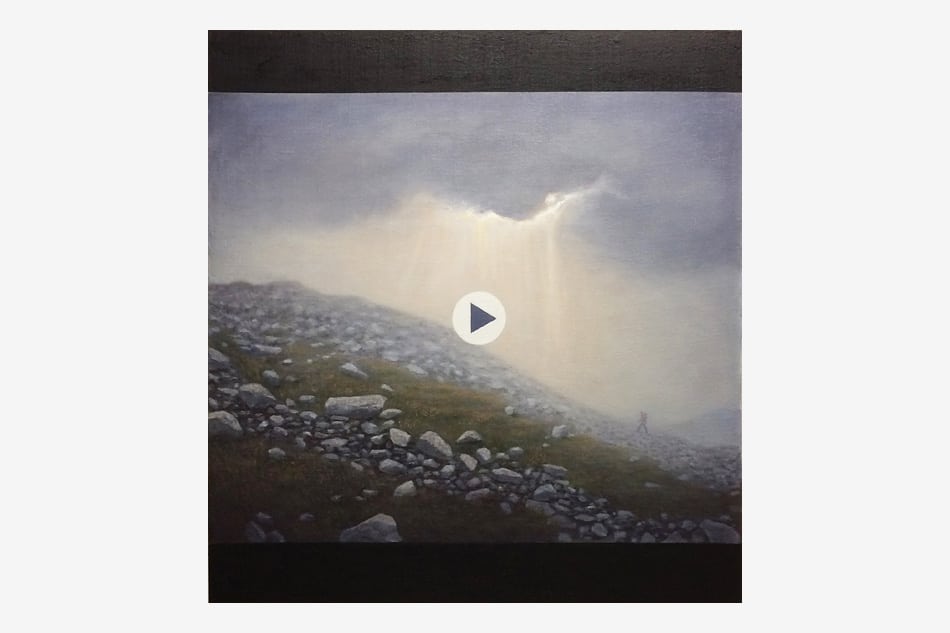

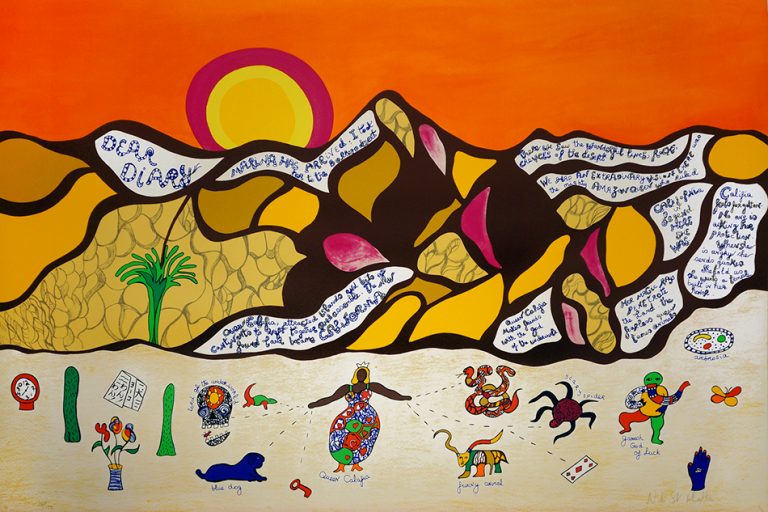

Saved Water, 2015, at Adelson Galleries, is one of the recent works into which Strauss has playfully incorporated the iconography of smartphones and apps. “I am interested in the digital-image disruption communicating the disruption of the natural world,” he says.

He was especially inspired by the Hudson River School and Luminist painters like George Inness and John Frederick Kensett, whose work he saw at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He began tackling larger, five-by-seven-foot pictures — a big jump from the small nocturnes — and adding mysterious, incandescent glows on the horizon to represent the lights of ever-encroaching civilization. This illumination often took the form of franchise signs, a theme repeated in McStop and the 1995 Descent. “This was my take on the look of America,” he says, “what I saw and what I found humorous.”

The play on words in the title of Oil Slick, a large diptych from 2002, underscores the dark humor with which Straus imbues the image: A tiny ship, set against a bright blue background, perches on the horizon, where the sky meets the dark and dominating sea, the inky waters rendered in thick black oil paint applied in loose brushstrokes and drips that both simulate the movement of the ocean and suggest an oil spill. “The message is very clear,” Straus says. “The smallness of the ship in this vast expanse and yet the damage it’s done.”

Recently, Straus has been experimenting with imagery derived from modern technology, pixelating his images, cropping and letterboxing his landscapes as if they were on Instagram, even playfully painting a play button in the middle of one of his peaceful seascapes. “I am interested in the digital-image disruption communicating the disruption of the natural world,” he says of these new meta forays. One of the works on display at the Adelson Galleries, the 2016 Glitch at the Edge of Antarctica, portrays a pristine arctic land- and seascape interrupted by bands of neon orange and yellow slicing through its middle. “I am making this realist landscape, and I am just kind of damaging it,” he says, explaining how he paints the image in full, takes a photograph of it, runs the photo through the Glitch app on his phone and then alters the original painting in stages according to what glitches have appeared; in this case, the painting went through nine iterations.

Straus’s technology-inspired paintings highlight how our extreme involvement with our devices has removed us from the glory of the world around us. “The more and more detached from nature you are,” he says “the more you are able to destroy it.”

An eponymous monograph, with text by Straus and art critic and curator Amei Wallach and published by Gli Ori, accompanies the exhibitions, whose timing feels perfect. “I believe that, at the moment, the art world is looking for artists who have depth, quality and something important to say,” Haime states.

For his part, Straus doesn’t think he will change the world with his art. “My art speaks to the converted,” he points out. ”I don’t think the art world is made up of a lot of climate change deniers. I am just trying to leave something behind that is about the most important issue of our time.”